Honey, I shrunk the npm package

Sep 27, 2023 · 11 minute read · CommentsHave you ever wondered what lies beneath the surface of an npm package? At its heart, it’s nothing more than a gzipped tarball. Working in software development, source code and binary artifacts are nearly always shipped as .tar.gz or .tgz files. And gzip compression is supported by every HTTP server and web browser out there. caniuse.com doesn’t even give statistics for support, it just says “supported in effectively all browsers”. But here’s the kicker: gzip is starting to show its age, making way for newer, more modern compression algorithms like Brotli and ZStandard. Now, imagine a world where npm embraces one of these new algorithms. In this blog post, I’ll dive into the realm of compression and explore the possibilities of modernising npm’s compression strategy.

What’s the competition?

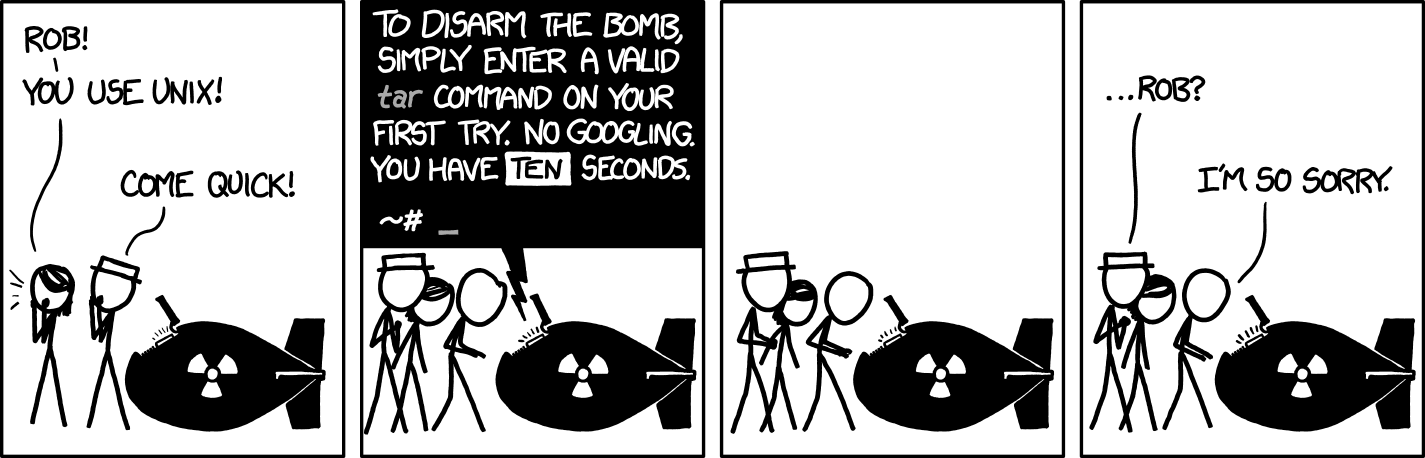

The two major players in this space are Brotli and ZStandard (or zstd for short). Brotli was released by Google in 2013 and zstd was released by Facebook in 2016. They’ve since been standardised, in RFC 7932 and RFC 8478 respectively, and have seen widespread use all over the software industry. It was actually the announcement by Arch Linux that they were going to start compressing their packages with zstd by default that made think about this in the first place. Arch Linux was by no means the first project, nor is it the only one. But to find out if it makes sense for the Node ecosystem, I need to do some benchmarks. And that means breaking out tar.

Benchmarking part 1

I’m going to start with tar and see what sort of comparisons I can get by switching gzip, Brotli, and zstd. I’ll test with the npm package of npm itself as it’s a pretty popular package, averaging over 4 million downloads a week, while also being quite large at around 11MB unpacked.

1$ curl --remote-name https://registry.npmjs.org/npm/-/npm-9.7.1.tgz

2$ ls -l --human npm-9.7.1.tgz

3-rw-r--r-- 1 jamie users 2.6M Jun 16 20:30 npm-9.7.1.tgz

4$ tar --extract --gzip --file npm-9.7.1.tgz

5$ du --summarize --human --apparent-size package

611M package

gzip is already giving good results, compressing 11MB to 2.6MB for a compression ratio of around 0.24. But what can the contenders do? I’m going to stick with the default options for now:

1$ brotli --version

2brotli 1.0.9

3$ tar --use-compress-program brotli --create --file npm-9.7.1.tar.br package

4$ zstd --version

5*** Zstandard CLI (64-bit) v1.5.5, by Yann Collet ***

6$ tar --use-compress-program zstd --create --file npm-9.7.1.tar.zst package

7$ ls -l --human npm-9.7.1.tgz npm-9.7.1.tar.br npm-9.7.1.tar.zst

8-rw-r--r-- 1 jamie users 1.6M Jun 16 21:14 npm-9.7.1.tar.br

9-rw-r--r-- 1 jamie users 2.3M Jun 16 21:14 npm-9.7.1.tar.zst

10-rw-r--r-- 1 jamie users 2.6M Jun 16 20:30 npm-9.7.1.tgz

Wow! With no configuration both Brotli and zstd come out ahead of gzip, but Brotli is the clear winner here. It manages a compression ratio of 0.15 versus zstd’s 0.21. In real terms that means a saving of around 1MB. That doesn’t sound like much, but at 4 million weekly downloads, that would save 4TB of bandwidth per week.

Benchmarking part 2: Electric boogaloo

The compression ratio is only telling half of the story. Actually, it’s a third of the story, but compression speed isn’t really a concern. Compression of a package only happens once, when a package is published, but decompression happens every time you run npm install. So any time saved decompressing packages means quicker install or build steps.

To test this, I’m going to use hyperfine, a command-line benchmarking tool. Decompressing each of the packages I created earlier 100 times should give me a good idea of the relative decompression speed.

1$ hyperfine --runs 100 --export-markdown hyperfine.md \

2 'tar --use-compress-program brotli --extract --file npm-9.7.1.tar.br --overwrite' \

3 'tar --use-compress-program zstd --extract --file npm-9.7.1.tar.zst --overwrite' \

4 'tar --use-compress-program gzip --extract --file npm-9.7.1.tgz --overwrite'

| Command | Mean [ms] | Min [ms] | Max [ms] | Relative |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| tar –use-compress-program brotli –extract –file npm-9.7.1.tar.br –overwrite | 51.6 ± 3.0 | 47.9 | 57.3 | 1.31 ± 0.12 |

| tar –use-compress-program zstd –extract –file npm-9.7.1.tar.zst –overwrite | 39.5 ± 3.0 | 33.5 | 51.8 | 1.00 |

| tar –use-compress-program gzip –extract –file npm-9.7.1.tgz –overwrite | 47.0 ± 1.7 | 44.0 | 54.9 | 1.19 ± 0.10 |

This time zstd comes out in front, followed by gzip and Brotli. This makes sense, as “real-time compression” is one of the big features that is touted in zstd’s documentation. While Brotli is 31% slower compared to zstd, in real terms it’s only 12ms. And compared to gzip, it’s only 5ms slower. To put that into context, you’d need a more than 1Gbps connection to make up for the 5ms loss it has in decompression compared with the 1MB it saves in package size.

Benchmarking part 3: This time it’s serious

Up until now I’ve just been looking at Brotli and zstd’s default settings, but both have a lot of knobs and dials that you can adjust to change the compression ratio and compression or decompression speed. Thankfully, the industry standard lzbench has got me covered. It can run through all of the different quality levels for each compressor, and spit out a nice table with all the data at the end.

But before I dive in, there are a few caveats I should point out. The first is that lzbench isn’t able to compress an entire directory like tar , so I opted to use lib/npm.js for this test. The second is that lzbench doesn’t include the gzip tool. Instead it uses zlib, the underlying gzip library. The last is that the versions of each compressor aren’t quite current. The latest version of zstd is 1.5.5, released on April 4th 2023, whereas lzbench uses version 1.4.5, released on May 22nd 2020. The latest version of Brotli is 1.0.9, released on August 27th 2020, whereas lzbench uses a version released on October 1st 2019.

1$ lzbench -o1 -ezlib/zstd/brotli package/lib/npm.js

Click to expand results

| Compressor name | Compression | Decompress. | Compr. size | Ratio | Filename |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| memcpy | 117330 MB/s | 121675 MB/s | 13141 | 100.00 | package/lib/npm.js |

| zlib 1.2.11 -1 | 332 MB/s | 950 MB/s | 5000 | 38.05 | package/lib/npm.js |

| zlib 1.2.11 -2 | 382 MB/s | 965 MB/s | 4876 | 37.11 | package/lib/npm.js |

| zlib 1.2.11 -3 | 304 MB/s | 986 MB/s | 4774 | 36.33 | package/lib/npm.js |

| zlib 1.2.11 -4 | 270 MB/s | 1009 MB/s | 4539 | 34.54 | package/lib/npm.js |

| zlib 1.2.11 -5 | 204 MB/s | 982 MB/s | 4452 | 33.88 | package/lib/npm.js |

| zlib 1.2.11 -6 | 150 MB/s | 983 MB/s | 4425 | 33.67 | package/lib/npm.js |

| zlib 1.2.11 -7 | 125 MB/s | 983 MB/s | 4421 | 33.64 | package/lib/npm.js |

| zlib 1.2.11 -8 | 92 MB/s | 989 MB/s | 4419 | 33.63 | package/lib/npm.js |

| zlib 1.2.11 -9 | 95 MB/s | 986 MB/s | 4419 | 33.63 | package/lib/npm.js |

| zstd 1.4.5 -1 | 594 MB/s | 1619 MB/s | 4793 | 36.47 | package/lib/npm.js |

| zstd 1.4.5 -2 | 556 MB/s | 1423 MB/s | 4881 | 37.14 | package/lib/npm.js |

| zstd 1.4.5 -3 | 510 MB/s | 1560 MB/s | 4686 | 35.66 | package/lib/npm.js |

| zstd 1.4.5 -4 | 338 MB/s | 1584 MB/s | 4510 | 34.32 | package/lib/npm.js |

| zstd 1.4.5 -5 | 275 MB/s | 1647 MB/s | 4455 | 33.90 | package/lib/npm.js |

| zstd 1.4.5 -6 | 216 MB/s | 1656 MB/s | 4439 | 33.78 | package/lib/npm.js |

| zstd 1.4.5 -7 | 140 MB/s | 1665 MB/s | 4422 | 33.65 | package/lib/npm.js |

| zstd 1.4.5 -8 | 101 MB/s | 1714 MB/s | 4416 | 33.60 | package/lib/npm.js |

| zstd 1.4.5 -9 | 97 MB/s | 1673 MB/s | 4410 | 33.56 | package/lib/npm.js |

| zstd 1.4.5 -10 | 97 MB/s | 1672 MB/s | 4410 | 33.56 | package/lib/npm.js |

| zstd 1.4.5 -11 | 37 MB/s | 1665 MB/s | 4371 | 33.26 | package/lib/npm.js |

| zstd 1.4.5 -12 | 27 MB/s | 1637 MB/s | 4336 | 33.00 | package/lib/npm.js |

| zstd 1.4.5 -13 | 20 MB/s | 1601 MB/s | 4310 | 32.80 | package/lib/npm.js |

| zstd 1.4.5 -14 | 18 MB/s | 1582 MB/s | 4309 | 32.79 | package/lib/npm.js |

| zstd 1.4.5 -15 | 18 MB/s | 1582 MB/s | 4309 | 32.79 | package/lib/npm.js |

| zstd 1.4.5 -16 | 9.03 MB/s | 1556 MB/s | 4305 | 32.76 | package/lib/npm.js |

| zstd 1.4.5 -17 | 8.86 MB/s | 1559 MB/s | 4305 | 32.76 | package/lib/npm.js |

| zstd 1.4.5 -18 | 8.86 MB/s | 1558 MB/s | 4305 | 32.76 | package/lib/npm.js |

| zstd 1.4.5 -19 | 8.86 MB/s | 1559 MB/s | 4305 | 32.76 | package/lib/npm.js |

| zstd 1.4.5 -20 | 8.85 MB/s | 1558 MB/s | 4305 | 32.76 | package/lib/npm.js |

| zstd 1.4.5 -21 | 8.86 MB/s | 1559 MB/s | 4305 | 32.76 | package/lib/npm.js |

| zstd 1.4.5 -22 | 8.86 MB/s | 1589 MB/s | 4305 | 32.76 | package/lib/npm.js |

| brotli 2019-10-01 -0 | 604 MB/s | 813 MB/s | 5182 | 39.43 | package/lib/npm.js |

| brotli 2019-10-01 -1 | 445 MB/s | 775 MB/s | 5148 | 39.18 | package/lib/npm.js |

| brotli 2019-10-01 -2 | 347 MB/s | 947 MB/s | 4727 | 35.97 | package/lib/npm.js |

| brotli 2019-10-01 -3 | 266 MB/s | 936 MB/s | 4645 | 35.35 | package/lib/npm.js |

| brotli 2019-10-01 -4 | 164 MB/s | 930 MB/s | 4559 | 34.69 | package/lib/npm.js |

| brotli 2019-10-01 -5 | 135 MB/s | 944 MB/s | 4276 | 32.54 | package/lib/npm.js |

| brotli 2019-10-01 -6 | 129 MB/s | 949 MB/s | 4257 | 32.39 | package/lib/npm.js |

| brotli 2019-10-01 -7 | 103 MB/s | 953 MB/s | 4244 | 32.30 | package/lib/npm.js |

| brotli 2019-10-01 -8 | 84 MB/s | 919 MB/s | 4240 | 32.27 | package/lib/npm.js |

| brotli 2019-10-01 -9 | 7.74 MB/s | 958 MB/s | 4237 | 32.24 | package/lib/npm.js |

| brotli 2019-10-01 -10 | 4.35 MB/s | 690 MB/s | 3916 | 29.80 | package/lib/npm.js |

| brotli 2019-10-01 -11 | 1.59 MB/s | 761 MB/s | 3808 | 28.98 | package/lib/npm.js |

This pretty much confirms what I’ve shown up to now. zstd is able to provide faster decompression speed than either gzip or Brotli, and slightly edge out gzip in compression ratio. Brotli, on the other hand, has comparable decompression speeds and compression ratio with gzip at lower quality levels, but at levels 10 and 11 it’s able to edge out both gzip and zstd’s compression ratio.

Everything is derivative

Now that I’ve finished with benchmarking, I need to step back and look at my original idea of replacing gzip as npm’s compression standard. As it turns out, Evan Hahn had a similar idea in 2022 and proposed an npm RFC. He proposed using Zopfli, a backwards-compatible gzip compression library, and Brotli’s older (and cooler 😎) sibling. Zopfli is able to produce smaller artifacts with the trade-off of a much slower compression speed. In theory an easy win for the npm ecosystem. And if you watch the RFC meeting recording or read the meeting notes, everyone seems hugely in favour of the proposal. However, the one big roadblock that prevents this RFC from being immediately accepted, and ultimately results in it being abandoned, is the lack of a native JavaScript implementation.

Learning from this earlier RFC and my results from benchmarking Brotli and zstd, what would it take to build a strong RFC of my own?

Putting it all together

Both Brotli and zstd’s reference implementations are written in C. And while there are a lot of ports on the npm registry using Emscripten or WASM, Brotli has an implementation in Node.js’s zlib module, and has done since Node.js 10.16.0, released in May 2019. I opened an issue in Node.js’s GitHub repo to add support for zstd, but it’ll take a long time to make its way into an LTS release, nevermind the rest of npm’s dependency chain. I was already leaning towards Brotli, but this just seals the deal.

Deciding on an algorithm is one thing, but implementing it is another. npm’s current support for gzip compression ultimately comes from Node.js itself. But the dependency chain between npm and Node.js is long and slightly different depending on if you’re packing or unpacking a package.

The dependency chain for packing, as in npm pack or npm publish, is:

npm → libnpmpack → pacote → tar → minizlib → zlib (Node.js)

But the dependency chain for unpacking (or ‘reifying’ as npm calls it), as in npm install or npm ci is:

npm → @npmcli/arborist → pacote → tar → minizlib → zlib (Node.js)

That’s quite a few packages that need to be updated, but thankfully the first steps have already been taken. Support for Brotli was added to minizlib 1.3.0 back in September 2019. I built on top of that and contributed Brotil support to tar. That is now available in version 6.2.0. It may take a while, but I can see a clear path forward.

The final issue is backwards compatibility. This wasn’t a concern with Evan Hahn’s RFC, as Zopfli generates backwards-compatible gzip files. However, Brotli is an entirely new compression format, so I’ll need to propose a very careful adoption plan. The process I can see is:

- Support for packing and unpacking is added in a minor release of the current version of npm

- Unpacking using Brotli is handled transparently

- Packing using Brotli is disabled by default and only enabled if one of the following are true:

- The

enginesfield inpackage.jsonis set to a version of npm that supports Brotli - The

enginesfield inpackage.jsonis set to a version of node that bundles a version of npm that supports Brotli - Brotli support is explicitly enabled in

.npmrc

- The

- Packing using Brotli is enabled by default in the next major release of npm after the LTS version of Node.js that bundles it goes out of support

Let’s say that Node.js 22 comes with npm 10, which has Brotli support. Node.js 22 will stop getting LTS updates in April 2027. Then, the next major version of npm after that date should enable Brotli packing by default.

I admit that this is an incredibly long transition period. However, it will guarantee that if you’re using a version of Node.js that is still being supported, there will be no visible impact to you. And it still allows early adopters to opt-in to Brotli support. But if anyone has other ideas about how to do this transition, I am open to suggestions.

What’s next?

As I wrap up my exploration into npm compression, I must admit that my journey has only just begun. To push the boundaries further, there are a lot more steps. First and foremost, I need to do some more extensive benchmarking with the top 250 most downloaded npm packages, instead of focusing on a single package. Once that’s complete, I need to draft an npm RFC and seek feedback from the wider community. If you’re interested in helping out, or just want to see how it’s going, you can follow me on Mastodon at @[email protected], or on Twitter at @Jamie_Magee.